In an opinion article published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution by researchers of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (UPF and CSIC) and the Institute of Marine Sciences (CSIC), with the participation of US and Canadian researchers, the authors show that despite the large efforts to sequence the genomes of as many organisms as possible, the knowledge of the large diversity within eukaryotes (higher organisms) is still extremely poor.

In an opinion article published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution by researchers of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (UPF and CSIC) and the Institute of Marine Sciences (CSIC), with the participation of US and Canadian researchers, the authors show that despite the large efforts to sequence the genomes of as many organisms as possible, the knowledge of the large diversity within eukaryotes (higher organisms) is still extremely poor.

As stated by Iñaki Ruiz Trillo, ICREA researcher and coordinator of the study, "a quarter of eukaryotic lineages do not have a single cultivated species and, what is worse, more than half of the eukaryotic groups do not have a single representative genome sequenced." This means that we lack half of the genetic information of eukaryotic lineages, which difficult the knowledge of biodiversity to the point, as Ruiz- Trillo keeps saying, " that we could doubt whether or not we know what represents to really be an eukaryote."

The authors argue in their article that the reason why the knowledge of the biodiversity of higher organisms is so poor is that there has been a significant bias due to several reasons. So far, science and scientists have worked with species closely related to Homo sapiens, or species potentially useful (plants, algae, fungi) or dangerous (parasites) to ourselves. Thus biodiversity knowledge has been built from an anthropocentric view. We should also add the difficulty to study some microbial species, such as those living by feeding bacteria (phagotrophs), which are very difficult to isolate and maintain in the laboratory.

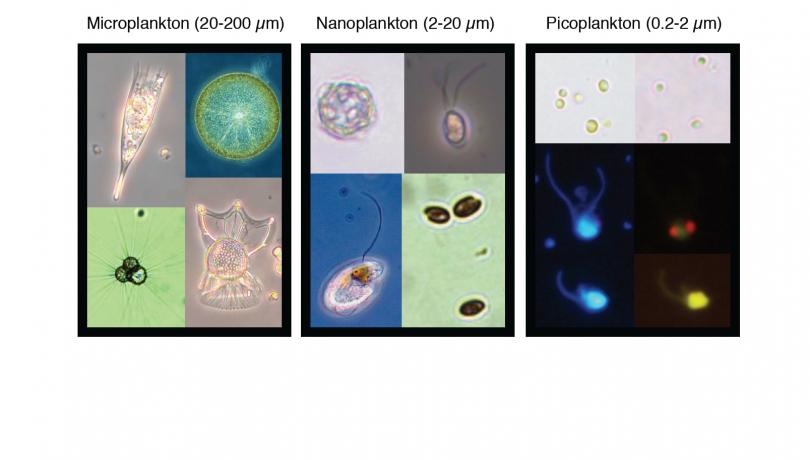

Researchers studying environmental microbial diversity have been aware of these limitations, and in fact much of the research performed by Javier del Campo, now at the University of British Columbia, has focused in the culturing bias of small phagotrophs. As commented by Ramon Massana, a scientist at the Institute of Marine Sciences, "seminal research on the diversity of marine eukaryotic microorganisms already unveiled a very large novelty, thus identifying a multitude of new species and taxonomic groups that had escaped the scrutiny of science."

Given all these limitations, the paper proposes a paradigm shift. Specifically, it proposes to sequence all living beings which have a cell culture (yeast, unicellular algae, etc...) and those which do not have any genome; devote more efforts to isolate new organisms from the environment; and finally use single cell genomics to retrieve data for those groups difficult to isolate. As Massana says, "the study of the genome of individual microbial cells, without the need to cultivate them, will represent a revolution in the fields of ecology and evolution, allowing to access to the gene content of the vast microbial uncultured majority, the " others" of our article."

Reference publication:

Javier del Campo, Michael E. Sieracki, Robert Molestina, Patrick Keeling, Ramon Massana, Iñaki Ruiz-Trillo (2014), " The others: our biased perspective of eukaryotic genomes", DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.03.006.